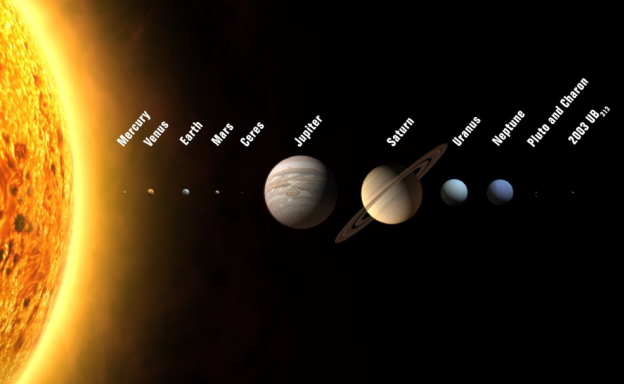

Now that we have a fair idea of the movement of the sky and its salient features, we now take a look at the various celestial objects you can find in the sky. We start our journey from the Solar System and its inhabitants, then move on to nearest stars, galaxies and so on.

The Sun

At the centre of the Solar System is the Sun, a fairly “average” star weighing about 300,000 times the Earth and 1.3 million times the volume. The Sun shines because it is continually producing energy in its core through hydrogen fusion.

The temperature at the surface of the Sun is 5780 K. In the core, the temperature is about 15 million degrees. The core extends from the Sun’s centre to about one-quarter of its radius, or about 175 million km. It contains about 1.6% of the Sun’s volume, but about one-half of its mass. The convection zone takes up the outer 30% of the Sun’s radius: the heat is transported by giant bubbles of gas circulating upwards, releasing their energy, then sinking down again.

At the surface, we see the granules from the convection, but we also often see giant sunspots.

Sunspots can be many times larger than the Earth. They appear dark because they are cooler than their bright surroundings, about 2000 K cooler. Most sunspots remain visible for only a dew days; others can last for weeks or months.

A very large sunspot group, about 13 times the size of Earth

Solar flares are tremendous explosions on the surface of the Sun. They typically last a few minutes and release energy across the whole EM spectrum, from radio to X-rays, as well as energetic particles.

The Moon

Aside from the Sun, the Moon is the brightest and most recognizable object in the sky. Many skilled stargazers have examined the surface of the Moon in detail for decades and still never tire of its stark beauty, and professional and amateur astronomers continue to study the history of our solar system as written into its rocky face.

Image of the Earth and Moon taken by the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite.

At about 1/4 the diameter of the Earth and some 250,000 miles away, the Moon spans just a tiny slice of sky, about half the width of your little finger held at arm’s length. Even with your unaided eye, you can see light and dark areas on the Moon. The light-colored areas are the lunar highlands, the oldest parts of the Moon’s surface. The highlands are peppered with craters made mostly by stray asteroids and comets left over from the solar system’s formation about 4 billion years ago.

The Moon cycles through phases once every 27 days or so. As it waxes from its “new” phase to full, it’s visible in the evening or night sky; as it wanes back to new, it’s mostly visible in the daytime.

The darker patches on the Moon are newer, about 3 billion years old. They are called the lunar maria (“MAH-ree-ah”) or seas, a misnomer since they are bone-dry and covered with fine dust. The maria were flooded with lava after the solar system had been mostly cleared out of stray material that smashed into the Moon’s surface. That’s why these younger regions are smoother and have far fewer impact craters.

The crescent Moon as it appears in binoculars. The dark areas are the “maria” or seas; the cratered lighter areas are the lunar highlands.

The seas of the Moon come into clear view with a pair of binoculars. So do about a dozen large craters. When the Moon is nearly full, you can see near the south-central part of the Moon (“south” is “down” for observers in the northern hemisphere) the crater Tycho, which has a series of “rays” that shoot out in all directions, giving the Moon the appearance of a peeled orange, with Tycho as the “pip”. The rays are material ejected when Tycho was created by a large asteroid impact about 110 million years ago.

The craters Copernicus and Tycho, and the Seas of Serenity and Tranquillity, just a few of the hundreds of features visible on the surface of the Moon

When the Moon is about a day or two past “first quarter” (when it appears half lit), another large crater comes into view near the equator of the Moon. This is the crater Copernicus, a large crater nearly 100 km across.

While binoculars show dozens of sights on the Moon, a small telescope reveals thousands, including craters of all shapes and sizes, arcing mountain ranges that tower thousands of feet above the lunar surface, and cracks and fault lines and strange domes that hint at past geological activity.

Beginners often believe the best time to observe the Moon is when it’s full. But that’s almost always the worst time. You’ll get the best views of the Moon along the terminator, the line that separates night from day. On the terminator, the craters and mountains stand out more clearly in the long shadows of lunar sunset or sunrise.

The terrestrial planets

The innermost planets are the terrestrial planets – the (at least approximately) Earth-like planets. The terrestrial planets are small, dense, rocky worlds, with much less atmosphere than the outer planets. They all lie in the inner solar system.

The four terrestrial planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, showing the relative sizes.

Mercury is the smallest planet in the Solar System, only slightly larger than the Moon. It is extremely dense, so must contain a very large core (~70% of its mass). Mercury orbits the Sun every 88.0 days, and rotates on its axis once every 58.7 days. This combines to give Mercury a day of 176 (Earth) days long, twice the length of the year!

Mercury has almost no atmosphere.

Mercury

Venus

Venus is almost exactly the same size as Earth. It is completely covered by clouds. The atmosphere on Venus consists of 96% CO2, 3% N2, and trace amounts of other chemicals; the clouds are not water vapour, but sulphuric acid. The pressure at the surface is 90 times the air pressure on Earth – the same pressure found at a depth of 1 km in Earth’s oceans. The temperature at the surface is 740 K (470o C), hot enough to melt lead. More than 80% of the planet is covered by vast low-lying areas of relatively featureless flows of lava. There are also about 150 giant volcanoes, up to 700 km in diameter and up to 5.5 km in height.

Mars is half the radius of the Earth and about 10% of the mass. It take nearly twice as long to orbit the Sun, but the length of its day and its axial tilt are very close to Earth’s. Mars has a thin atmosphere – 1/150th the pressure of Earth’s – which is primarily CO2, with small amounts of nitrogen and argon.

Mars is a planet of extremes. It has the tallest mountain in the Solar System: Olympus Mons, 27 km high; the biggest canyon in the Solar System: Valles Marineris, over 4000 km long the deepest hole in the Solar System: Hellas Basin, a giant impact basin 8.2 km below the surrounding uplands. It seems clear that Mars had flowing liquid on its surface at least at some stage during its history, however liquid water cannot exist on Mars at its current temperature and pressure. For Mars to have had surface water, its atmosphere must have been significantly thicker.

The giant planets

Jupiter is the most massive of the planets, 2.5 times the mass of the other planets combined. Jupiter’s visible surface is not solid: it is a gas giant. Everything visible on the planet is a cloud.

True colour picture of Jupiter, taken by Cassini on its way to Saturn during closest approach. The smallest features visible are only 60 km across.

The Great Red Spot is a giant storm that has been raging for at least 350 years, since its discovery by Robert Hooke in 1664.

Comparison between the size of Earth and the Great Red Spot.

Jupiter has (at least) 63 moons, the four largest of which are known as the Galilean satellites. Three of these moons are bigger than Earth’s moon, and Ganymede is larger than Mercury. Io takes only 1.8 days to orbit Jupiter; Europa, Ganymede and Callisto take 2x, 4x and 9.3x as long to go around. All four moons are worlds in their own right, and quite different from each other. Callisto is covered in icy craters; while the surface of Ganymede shows both craters and ice-flow features. Europa is completely covered with ice – the smoothest object in the Solar System. Io is covered with volcanos: the most volcanically active world in the Solar System. Tidal stress keeps the interior of Io molten; Io’s red-orange colour is from sulphur and its compounds.

Saturn is almost as large as Jupiter (85% of the diameter), but has only 30% of Jupiter’s mass. Like Jupiter, it is a gas giant. The most obvious feature of Saturn are the immense rings.

The ring system is remarkably complex, and is still poorly understood. It was Huygens who, around 1655, recognized that Saturn was “girdled by a thin, flat ring, nowhere touching it.”

Saturn’s equator is tilted relative to its orbit by 27º. As Saturn moves along its orbit, first one hemisphere, then the other is tilted towards the Sun. From the Earth, we can see Saturn’s rings open up from edge-on to nearly fully open, then close again to a thin line as Saturn moves along its 29 year orbit.

The rings are extremely thin – possibly only 10 m thick – and composed almost entirely of chunks of water ice. The gaps in the rings are kept clear by Saturn’s many moons, either orbiting within them, or clearing them via gravity.

Like Jupiter, Saturn has a large family of moons. Titan is the largest (larger than Mercury, and second only to Ganymede); then there are six large icy moons, and a whole host of small ones. Sixteen satellites orbit within the main rings themselves.

Beyond Saturn are the two ice giants: Uranus and Neptune. They are very similar in size, though Neptune is slightly more massive. Methane gives the planets their blue-green or blue appearance.

Unlike the other planets, Uranus’ axis of rotation is tilted to lie almost in the plane of its orbit. This means it has very bizarre seasons, with each pole being sunlit for 42 (Earth) years. During this time, the pole receives more light than the equator, before being plunged into darkness for the next 42 years.

Neptune has thirteen moons, only two visible from Earth – Triton and Nereid. Both have peculiar orbits: Nereid’s orbit is highly eccentric, and Triton is unique among large planetary satellites because it orbits backwards – opposite to the sense of the planet’s rotation.